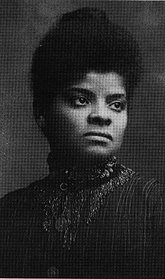

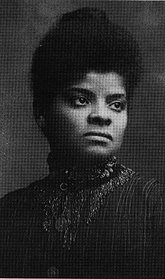

Ida Bell Wells-Barnett was born in 1862, the oldest of eight children of the slave couple Jim Wells and Lizzie Warrenton. Raised in the postbellum South, her parents believed in the education of their children.

In 1879, Ida and two of her younger siblings moved to Memphis to live with an aunt, and Ida became a teacher. In 1889, she bought one-third interest in the Memphis

Free Speech and Headlight. Arguing that inadequate buildings and improperly trained teachers contributed to the mediocre education of black children, she alienated conservative black leaders and lost her teaching position. Forced to rely on her own resources, she canvassed the South for subscriptions to her newspaper.

A life-altering event occurred in 1892. Three of her colleagues--Thomas Moss, Calvin McDowell, and Henry Seward, successful managers of a grocery business in the black section of town--were lynched. Until this time, like so many other Americans, Ida had accepted the common place charge that black men were lynched because they had tried to rape white women. However, this time Ida knew the true story behind the lynching of Moss, McDowell and Seward, and it was greed. The white owner of a competing grocery store wanted to eliminate the competition. Questioning her long-held belief, Ida investigated the cause of lynchings throughout the South and concluded "lynching was a racist device for eliminating financially independent Black Americans."

In her editorial, Ida urged black citizens of Memphis to leave the town that would protect neither their lives nor their property, nor give them a fair trial in the courts when accused by a white person. She also wrote a scathing editorial attacking white female purity and suggested it was possible for white women to be attracted to black men. (You go, girl!)

Her newspaper office was was destroyed and threats made against her life. Luckily she was enroute to Philadelphia for a conference when this happened. She never returned to Memphis. Instead, she moved to New York and continued her expose on lynching, culminating in the story "Southern Horrors: Lynch Law In All Its Phases."

She went on to become a leading national figure in African-American civil rights and women's rights movements, as well as the fight for economic rights for all. Active in the women's suffrage movement, Ida repeatedly forced white women to face the racism in their suffrage organizations. Believing that white people could not be relied upon to give equal opportunities for black people, she supported the movement of blacks to organize themselves and take the lead in fighting for their own equality.

Active in the women's club movement, Ida opened the Negro Fellowship League (1910) to provide lodging, recreational facilities, a reading room, and employment for black migrant males, work that eventually was taken over by a better funded Young Men's Christian Association (1913) and the Urban League (1916). Also active in the Civil Rights movement, Ida signed the call for the national conference that led to the founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Ida Bell Wells-Barnett was another woman who saw a need, and stepped up to the challenge.

P.S. Don't forget to come over to

The Raven and read some really great excerpts today through Sunday. And if you're not a member of my readers group, get thee over to

Indulge Authors right now and join!

Careful Wishes is the story of Addie Langdon, who has a telepathic empathy for animals that makes her perfect for her job. She and her twin sisters are part owners, along with their twin cousins Brandt and Turner De Winton, of Friends, Incorporated, a private investigation firm specializing in finding things--and people--who are lost. Addie has lost Donovan Miles because of her gift. Or has she...?

Careful Wishes is the story of Addie Langdon, who has a telepathic empathy for animals that makes her perfect for her job. She and her twin sisters are part owners, along with their twin cousins Brandt and Turner De Winton, of Friends, Incorporated, a private investigation firm specializing in finding things--and people--who are lost. Addie has lost Donovan Miles because of her gift. Or has she...?